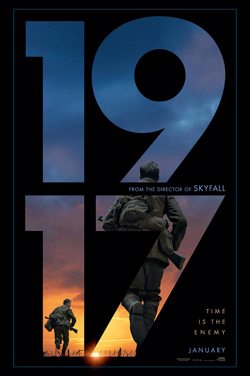

There are war movies, and then there are war movies like 1917 that challenge us never to break eye contact with the on-screen drama. Director Sam Mendes' World War I drama unfolds in the illusion of one shot – in fact, it's a series of astonishingly complicated long takes that are seamlessly interwoven, taking us from the German front line into booby-trapped trenches and beyond.

The shifting of the physical landscape unfolds through the eyes of two young British soldiers, played by Pride's George MacKay and Game of Thrones' Dean-Charles Chapman. They're tasked with delivering a vital message to a British battalion who are about to walk into a German ambush – on the shoulders of these two men rests the fate of 1,600 others. It's a powerful reflection of selfless heroism and unblinking virtue in the midst of a horrendous conflict that changed the nature of warfare overnight.

The lack of obvious edit points in the movie gives it an unblinking, relentlessly suspenseful atmosphere – we don't want to wrench our eyes from the screen lest we miss the subtlest detail or character beat that will inform our wider understanding of the story.

The key word is immersion: master cinematographer Roger Deakins (Blade Runner 2049) finds a multitude of emotional registers as the physical environment morphs, from the relative calm of a deserted French farmhouse to an almost surreal, terrifying chase inside an abandoned town, whose rubble-strewn alleyways and skeletal structures take on the hellish hues of fire and distress flares.

We're compelled to absorb every physical and emotional facet of the anguished story playing out in front of us, and working in tandem with Deakins and Mendes is esteemed editor Lee Smith. He sculpts out a movie that approximates real time, and Smith has past form in this area, having collaborated to acclaimed effect with director Christopher Nolan several times before.

Nolan is famous for treating the concept of time as his own personal toy box – take Inception, for instance, in which multiple layers of one's consciousness unfold at different speeds relative to each other. Smith's deft editing makes a fabulously intricate jigsaw of the film's contradictions, zipping between the external world and the interior mind that keeps the audience on their toes.

Then there was the interplay between three different timelines in Christopher Nolan's riveting World War II thriller Dunkirk, for which Smith won an Oscar. Conflicts on land, sea and air overlap, Smith's editing constantly intercutting between victory and tragedy in a manner that feels authentic to the unpredictable patterns of modern warfare.

Smith's presence on 1917 complements his earlier work on Inception and Dunkirk (not to mention Interstellar, the Dark Knight trilogy and The Prestige), yet also in many ways goes against it. Like those Nolan films, 1917 is a movie driven by the philosophical conceit of time itself, yet unlike those movies, here there is an illusion of unity, with next to no break points in the fabric of the narrative.

Speaking to Cineworld from the red carpet premiere of 1917, Smith addressed the challenges of editing a movie that seemingly plays out in one shot.

"We'd always intended this experience to feel as if you, the viewer, was a participant," Smith explained. "And really the only way to do that is not edit. It was an idea [Sam Mendes] had, and we'd tried it before on [24th James Bond movie] Spectre, during the opening sequence. And it was very difficult! So it was like, what a great idea – let's do an entire movie like that!

"I remember reading the script for 1917 and forgetting that it was supposed to be one take. But the whole point of it was, we were watching it on a daily basis, and if we ever felt a need to cut, I had to ring Sam and justify it. There was a lot of pressure, really on a daily basis, as we were making the film day by day."

Smith also explained that the journey from script to screen was seamless, bar "some modifications while we were shooting". He described the process of "organically" working on the film, adding: "The film was being built in the edit as we were filming. I was putting music and sound effects on it and if it didn't work, if it didn't have the emotional kick, you're not going to be able to get it later. It was really weird".

So how did the experience of working on 1917 compare to the other blockbusters Smith has worked on? "Completely different", is how he describes it. "I've never had to know what's working that far in advance before. My job is to sort of know what's working, but usually you've got the entire post-production period to work that out. And usually I've got a million feet of film to choose from.

"On this film, we had to know ahead of time what was working, and we had to keep reminding ourselves that one can't keep quiet about it. One has to speak up. If there's an inkling that something's not working, now's the time to say so. That was every day for the entire shoot".

That invisible hand of veteran editor Smith is one of the most powerful tools in 1917's arsenal, approximating our own perception of time and reality. It draws us further into a depiction of a devastating real-life conflict, from which we become more and more distant with each passing year.

It remains to be seen if Smith, along with Mendes and Deakins, will pick up his second Oscar, but there's no denying the film's technical virtuosity.

Click here to book your tickets for 1917, on release now in Cineworld. Don't forget to tweet us your reactions to the film @Cineworld.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)